education

vaping & electronic cigarettes

On This Page

What is vaping?

Electronic cigarettes (also known as e-cigarettes, vapes, or vapor products) are an alternative to tobacco cigarettes.

Nearly all vaping devices operate on a fairly simple principle: A liquid substance (commonly called e-liquid) is converted to an aerosol through the process of heating – like water turning to steam.

When someone uses an e-cigarette, the device’s battery sends an electric current to a wire coil wrapped around liquid-soaked wicking material, causing it to heat up. Once the coil becomes hot enough, it heats the surrounding liquid into an aerosol. The aerosol, or vapor, is then inhaled by the user.

Because people who vape inhale an aerosol, and not smoke, they often refer to themselves as “vapers” to distinguish themselves from people who smoke.

View our Electronic Cigarettes Frequently Asked Questions for more information.

What is vaping used for & who does it?

Smoking Cessation

The first commercially successful electronic cigarette was invented in 2003 by a Chinese pharmacist named Hon Lik. Hon’s father, who smoked heavily for many years, had recently died, and Hon wanted to develop a device that could help him stop smoking, in an effort to avoid his father’s fate.

By 2007 vapor products had found their way to Europe and the United States, and in the years that followed enthusiasts who successfully used them to stop smoking continued to refine and improve the technology, giving us the wide array of vapor products we have today.

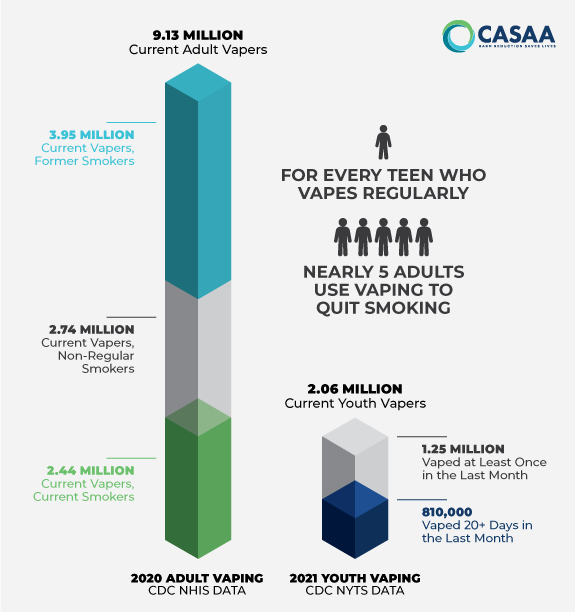

Public health and government officials often claim “there is no evidence that e-cigarettes help people quit smoking.” But according to recent studies there is evidence showing that vaping is effective in helping people give up cigarettes. Moreover, recent industry data shows that more than three million people in the United States have switched from smoking to vaping.

Thousands of people report quitting smoking because of e-cigarettes in the testimonials section of this website. According to survey data, hundreds of thousands more are estimated to have done the same.

It is mind boggling to claim that hundreds of thousands of people are somehow confused or wrong about how e-cigarettes helped them become ex-smokers.

The people who are not convinced that e-cigarettes help people quit smoking are simply not thinking like good scientists and have a highly biased conceptualization about what smoking is and how people quit. They tend to think of smoking as a medical problem akin to a disease for which a cure should be sought. This limits the type of research they find acceptable in determining if vaping has value in helping people quit smoking.

About Vapers

A number of surveys have been conducted in the United States and United Kingdom to help characterize which groups of people are vaping. The data from these surveys is consistent enough to make some general conclusions:

- The vast majority of daily vapers are people who smoke or used to smoke. (This is unsurprising given the similarity of nicotine vapor products to tobacco cigarettes.)

- A large number of daily vapers are people who used to smoke, but now vape exclusively.

A large portion of people who vape continue smoking cigarettes. At the time of this writing, they make up roughly half of all people who vape. These people are referred to as “dual users.” The fact that there are a sizable number of dual users is also unsurprising. Some dual users are simply vaping in places or situations where smoking is inappropriate, but continue to smoke cigarettes when they are able to. Other dual users are actively attempting to stop smoking, but continue to smoke while they experiment with vaping.

By far, the smallest group of vapers are those who have never smoked.

See more results from the 2019 EcigIntelligence Survey.

Youth Usage

CASAA supports laws that prohibit underaged sale (<18) and urges strict enforcement of these laws. However, CASAA does not support laws that criminalize people of any age possessing or using nicotine products.

History shows us that youth have a knack for getting ahold of and using products they are forbidden to have (e.g., cigarettes, alcohol, drugs). The same is true of vapor products. Young people are an especially curious bunch and many, especially those approaching adulthood, are naturally attracted to products and activities that are considered strictly for adults. So it is no surprise that many young people have tried vaping.

Accurate information about the number of young people vaping nicotine is often misunderstood due to the publication of cherry-picked data, media hype, and agenda-driven conclusions.

The most egregious spin is applied to the data on “current vaping.” The CDC’s National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) is the source cited for the majority of vaping and tobacco usage data on young people. This survey asks middle and high schoolers if they have vaped, even once, within the last 30 days, and if the answer is “yes” they are recorded as a “current user.” Even if they never touch another vapor device in their life, they are recorded for that year as “currently vaping.” Using this data as a metric is highly misleading considering the propensity for youth experimentation, and the perception by the public that “current vaping” means they are vaping regularly or daily. Imagine having 1 or 2 alcoholic beverages in a month and being called a “current alcoholic.”

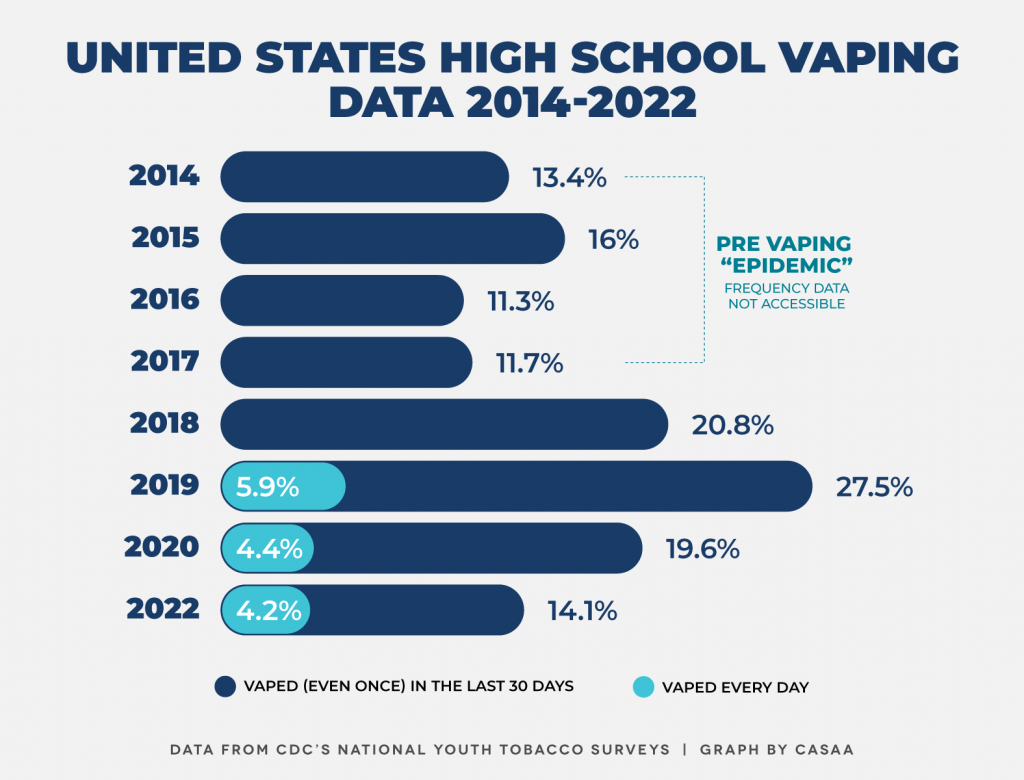

The NYTS does collect data on how frequently youth are actually using vapor products, but this additional information has been omitted from the published findings in the past, and more recently, is not emphasized when it is published. This more detailed frequency data shows us that while 14.1% of high schoolers in 2022 were recorded as “currently vaping,” only 6.5% used vapor products “frequently” (on 20 or more days out of the last 30), and even less (4.2%) use vapor products on a daily basis.

Newly available data for 2022 shows a dramatic 48% decrease in high school “current vaping” since 2019, putting the current usage rate back to “pre-epidemic” levels.

The Gateway Theory

The “Gateway Theory” proposed by some researchers claims that youth who vape will be more likely to start smoking cigarettes. They come to this conclusion by looking at youth who vaped and also smoked, and creating a causal link between the two. This also is extremely misleading because correlation does not equal causation. If you were to examine the number of adults who use illicit drugs and those who also drink alcohol you’d find a dramatic correlation – many people do both. But that does not mean that drinking alcohol is a gateway to drug use.

It is not at all surprising that someone who would be interested in vaping would also be interested in smoking, given their similarity, or that teenagers would try both, being novelty-seekers in general. It does not mean that experimenting with one product causes someone to try the other.

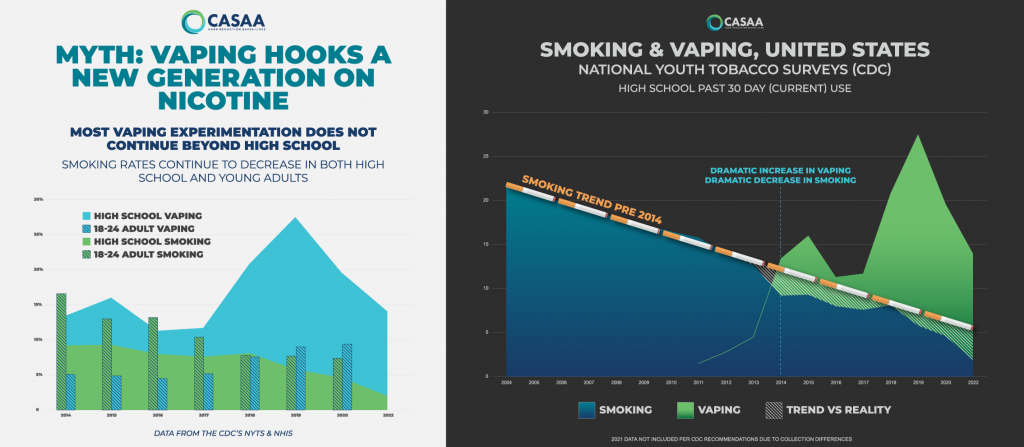

Moreover, the steep decline of cigarette smoking in young people, coupled with the fact that the majority who vape have a history of smoking, implies that vapor products are likely an off-ramp from smoking cigarettes, not a gateway.

Additionally, a major flaw in the data presented by the NYTS is that it is unable to definitively say what young people are vaping. Vaping cannabis and THC has also become increasingly popular in recent years, and since vapor products and e-cigarettes are often conflated with cannabis vaping products, it’s possible some youth may be reporting cannabis vaping, not nicotine vaping.

What are vapor products?

Vapor products come in a wide range of options.

From small to large, there is a device and e-liquid out there to meet the needs of a diverse consumer base.

While some people prefer the convenience of plug-and-play small devices that come pre-filled with liquid, other people require customizability and prefer the enhanced performance of more advanced, open-system products.

Whether you prefer to carry your e-cigarette in a shirt pocket or you do best with a setup that requires its own handbag, there is a liquid and device combination out there for almost anyone who wants to switch from smoking to vaping.

Devices

Vaping devices come in all shapes and sizes and can be roughly categorized according to their simplicity, customizability, and capacity. An important distinction between devices is whether they are a closed or open system.

Closed system devices are not designed for modification by the user. The battery, coil, and cartridge/pod containing the e-liquid are self-contained. The only flexibility is being able to switch pre-filled pods/cartridges to change flavor or nicotine strength.

In contrast, all aspects of open system devices can potentially be changed to suit one’s preferences and needs – everything from the resistance and material of the coil, the type of wicking material, the style of airflow on the device, to the power of the batteries, and then some.

Lithium ion batteries are used in everything from e-cigarettes, to cell phones, to laptop computers, to the Boeing 787 Dreamliner. What the batteries in all these devices have in common is that they very rarely catch fire or explode. E-cigarettes are a relatively new product, so when their batteries catch fire or explode it makes headlines. Many times these incidents are the result of improper charging (using the wrong adapter) or storage (carrying a battery in a pocket with other metal objects). But, how common is it for e-cigarette batteries to explode?

According to The U.S. Fire Administration, between 2009 and 2014 there were a total of 25 incidents of fire and explosions involving e-cigarette batteries, leading to nine injuries and no deaths. In comparison, the Consumer Product Safety Commission has issued 40 recalls since 2002 on laptop and notebook computers due to fire and burn hazards. Lithium ion battery fires and explosions, for the most part, are of little concern for the vast majority of those who use an e-cigarette, laptop, cell phone, or take a flight on a Boeing 787. The industry that makes these batteries is working to make them safer. CASAA is working with others to develop battery safety guidelines for e-cigarette users. Meanwhile, there is no reason to think this problem is especially confined or more highly concentrated in vaping devices.

E-Liquids

The liquids used in e-cigarettes, no matter what the device, typically include a combination of four main ingredients: propylene glycol (PG), vegetable glycerin (VG), flavorings, and (optional) nicotine. The combination and ratio of these ingredients depend on the preferences of the user.

Propylene Glycol

Propylene glycol (PG) is manufactured in large quantities because it has a wide variety of uses from food products, to drugs, to entertainment. It imparts little flavor of its own, and keeps packaged food from drying out. In many oral and topical drugs it’s used as a stabilizer. In theater productions PG is used to simulate fog. E-cigarette liquids contain PG because it mixes well with flavoring ingredients, and when heated, produces a smoke-like vapor. Because it is a slight irritant, it also mimics the sensation of inhaling cigarette smoke.

Vegetable Glycerin

With similar properties as PG, vegetable glycerin (VG), which is almost exclusively derived from plants, is widely used as a food additive and in drug manufacture. It also imparts a sweet flavor and helps keep foods moist. It is used in e-cigarette liquids for much the same reason as PG. Because VG is thicker than PG, vapers use an e-liquid with a higher VG content when they want to exhale vapor plumes that are thicker and more voluminous.

Flavorings

Flavorings are themselves combinations of different flavoring chemicals, and almost all flavoring ingredients used in e-liquids are the same or similar ones used in foods and drinks. There are thousands of flavors used in the food/beverage industry, and the same is true for e-liquids manufactured for use in vapor products. One medium-sized company can easily offer more than 30,000 flavor/nicotine combinations. The most common categories are: fruits, dessert/bakery, sweets/candy, custards/ yogurts, breakfast, mint/menthol, beverages, tobacco, and savory/spice.

Nicotine

E-cigarettes are designed as a low-risk alternative to smoking, and because almost all vapers currently smoke or are vaping to quit and enjoy the effects of nicotine, nicotine is an important ingredient for many of them. A practical advantage over tobacco cigarettes, e-cigarette devices allow users to fairly precisely control the amount of nicotine they use.

E-cigarettes are available in a range of nicotine strengths allowing people to choose the amount of nicotine delivered to meet their personal needs. People who use e-cigarettes to quit smoking often start with a higher nicotine level and may gradually reduce the nicotine as they find themselves less dependent on cigarettes. This behavior is similar to that modeled by Nicotine Replacement Therapies (NRTs) like patches, gums, and lozenges. The striking difference, however, is that people who choose vaping typically do so enthusiastically, as opposed to NRTs which often require coercion from doctors or other societal pressures.

Why Flavors Matter

While many people new to vaping might initially choose flavors similar to tobacco, the vast majority eventually move on to other flavor categories in an effort to distance themselves from the experience of smoking cigarettes.

Various polls conducted over the years show a consistent preference for fruit or dessert flavors among adults who vape. One of the key issues that makes vaping a more personal experience is the availability of a wide range of different flavors.

Many people enjoy more than one flavor during their day, and the ability to experiment with new flavors keeps vapers engaged (as opposed to returning to smoking). Research supports the anecdotal evidence that adults who vaped flavored vapor products are more likely to quit smoking.

What are the risks associated with vaping?

Chemical analysis of e-cigarette vapor, and the likelihood that these chemicals are not causing harm, is a solid foundation for evaluating potential risks. But the story is incomplete without looking at the effects these devices are having on people in the real world. After all, what we are ultimately interested in is what happens to people when they use e-cigarettes.

Scientists have amassed a great deal of data from people who vape. This information comes by way of:

- Self-reports (surveys asking about use, symptoms, and other negative or positive consequences); and,

- medical and scientific data (reports from clinicians and scientists about what they’ve observed in people who vape)

What we’re looking for is a clear pattern of symptoms or illnesses that occur in people who vape, and is not found in non-vapers.

Millions of people around the world are vaping, some for 10+ years, without experiencing negative health effects. Of course, some people report minor issues like throat irritation or coughing, but these tend to go away with time, discontinued use, changing devices, or trying a different e-liquid. Making sure to drink plenty of water helps, too. But, as noted, these issues are typically quite minor, and many (if not most) people who switch from smoking to vaping report a gradual reversal of symptoms like coughing and shortness of breath.

What You Should Know About E-cigarettes and EVALI

Clearing up misinformation and myths

Out of the millions of people who vape worldwide, there have been few reports of anyone suffering lasting or permanent harm resulting from intended use of a properly functioning e-cigarette.

This does not include accidental poisonings or catastrophic device failure like battery explosions. These problems, while rare, are separate safety considerations. This also does not include the 2019 outbreak of lung injuries linked to illicit THC oil cartridges (and not nicotine-containing e-cigarettes). Notably, the so-called “EVALI” crisis almost exclusively affected the United States. Millions of people around the world continue to use vapor products with no similar incidents of mass injury.

We have information from millions of people vaping under normal use conditions with almost no serious problems reported. Because of this we can be confident that nicotine vaping poses few short-term health risks.

Assessing the risk of long-term use requires more information. In the interim, we are making predictions based on incomplete, but best available data. It is possible that in 20 or 30 years nicotine vaping could become identified as causing some harm, but those harms would have to be very serious and significant in order to outweigh the public health benefit associated with people reducing or eliminating their smoking habit.

Replicating real-world conditions is a problem inherent in almost all research investigating potential harm resulting from long-term vaping. Assuming these studies are well conducted and they’ve managed to create laboratory conditions that mimic how things work in the complex real world (most do not), and they’ve found something that suggests a possible cause of harm, then what they have found is a hypothesis about something that might cause harm. But in press releases of scientists that the media turns into news, it is strongly implied they have found evidence of harm. A hypothesis is not evidence, though.

What we’re seeing in the media today is a series of educated (and many not-so-educated) guesses about the long-term risks of vaping and using nicotine. But well-trained scientists know better than to accept claims in splashy headlines. They know the results from single studies can only point the way to further research (at best). Individual studies can’t be definitive in their conclusions about long-term harm either. In reality, research shows that at present, there is no credible reason to strongly suspect e-cigarettes pose significant long-term health risks. This is not the same as saying it is impossible for there to be any long-term risks, only that it appears that long-term risks are unlikely.

This puts e-cigarettes in the same position as other new products released on the market. Consider new prescription drugs, cell phones, and artificial sweeteners. It was fairly clear what these things were and how they worked. No short-term harms were identified, nor were there any convincing reasons to suspect they had a high likelihood of causing long-term harm. So they were allowed on the market with the knowledge it was possible that they may cause some harm following long-term use. We allow this because there would never be a new drug or product ever released if we had to be 100% certain there would be no long-term risks. Moreover, new products like these have a high degree of probability of improving people’s lives compared to the potential risks. In other words, the potential benefits outweigh the hypothetical harms. This is especially true of e-cigarettes, which are helping us replace a known harmful activity with something demonstrably safer.

Risks for Vapers

Making an accurate estimate of the health risks of consumer products such as food, beverages, consumer goods, and medication is a complex process. It involves reams of data from many fields of study and careful scientific analysis.Vapor products have been on the market for more than ten years, becoming very popular only in the past five. By some accounts, ten years is not enough time to identify all the potential health risks vaping may pose. But we know a lot already about what’s in e-liquid, how the devices work, and how people use them.

We can be very confident that vapor products cannot be as dangerous as cigarette smoking.

The Royal College of Physicians, in their extensive review of the evidence in 2016, says “the available data suggest that [nicotine vapor products] are unlikely to exceed 5% [of the health risk] associated with smoked tobacco products, and may well be substantially lower than this figure.” The best available estimate of vaping risk would be to compare it to another popular form of non-combustible tobacco use: smokeless tobacco. Strong epidemiological evidence puts the health risk of moist, pasteurized smokeless tobacco (also called snus) used in Sweden and the United States at approximately 1% compared to the risk of smoking.

Nicotine Without Smoke: Tobacco Harm Reduction

Royal College of Physicians

Risks for Bystanders

Igor Burstyn of Drexel University reviewed over 9000 measurements of the chemicals in e-cigarettes. Burstyn focused on contaminants associated with a risk to health and compared the values observed to occupational workplace safety standards. To put the results in context Burstyn compared a vaper’s deliberate exposure to these contaminants to what a person might experience involuntarily in a workplace. He concluded that even after decades of exposure the risk to bystanders would not justify any attention. Indeed, the values obtained were between 1% and 5% of the levels needed to cause a health concern in a workplace. Even so, Burstyn was cautious about the common ingredients PG and VG. There is no established level of exposure for these ingredients that represents a threat to health. Before e-cigarettes, inhaling a vapor of PG or VG was such a rare event, there was no need to establish a standard. It is commonly understood that PG and VG are generally benign substances, but only recently have large numbers of people been inhaling them. In other words, we have no good reason to suspect inhaling PG or VG is harmful, but because this is a new kind of exposure, the cautious thing to do is the same thing we do with new drugs consumed by large numbers of people. We observe the users and look for signs and reports to see if any negative health effects are emerging.

We know from the Burstyn study how low the risks are for those who directly inhale e-cigarette vapor. Bystanders have far less exposure to e-cigarette vapor for three simple reasons: (1) what an e-cigarette user exhales has less volume than what they inhale because some of the vapor remains inside the body; (2) what the user exhales is immediately diluted by the ambient air; and (3) e-cigarette aerosol is liquid droplets that evaporate fairly quickly. Using Burstyn’s estimate as a guide, a bystander would have to be in a room with 100 to 1000 people vaping to inhale in one breath a similar amount of vapor an e-cigarette user inhales in a single puff. This makes exposure risks to bystanders virtually zero in any real-life situation.

Facts & Myths

False. As of August 8, 2016, all new nicotine products introduced into the market after February 15, 2007 must go through a premarket review by FDA. While PMTA enforcement did not begin until September 2019, vapor products have existed under some form of regulation at the state and local levels since 2009. If marketed as a smoking cessation or any other therapeutic product, nicotine falls under FDA’s jurisdiction over drugs and devices. The US District Court for the District of Columbia stated as much in its ruling against the FDA in 2010 when the agency attempted to stop e-cigarettes from being imported to the US as “unapproved drugs/devices.”

True. E-cigarettes and vapor products are a form of Tobacco Harm Reduction, designed as a safer alternative to smoking. When discussing the safety of vaping, the comparison must always be to cigarette smoking. Numerous studies show that people who vape are exposed to significantly lower levels of toxicants and carcinogens than people who smoke, thus making them safer than smoking. Safer does not mean 100% safe, but for people who smoke, the science tells us switching completely can be extremely beneficial.

False. A variety of studies conclude that vapor products do help people quit smoking. Most notable is a randomized controlled clinical trial published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2019 which found that nicotine-containing vapor products were nearly twice as effective as traditional nicotine replacement therapies (like gums and patches) to help people quit smoking. Additionally, the highly respected Cochrane Library published an updated analysis of e-cigarettes for smoking cessation in 2020, which found moderate-certainty evidence that quit rates were higher for people using nicotine vapor products than with traditional nicotine replacement therapies. Cochrane’s conclusions were based on a meta-analysis of 50 different studies across 13 different countries.

False. The first commercially successful e-cigarette was invented by Chinese pharmacist Hon Lik in 2003 to help him quit smoking. Independent consumers and small businesses around the world, but especially in the United States, innovated and grew the product category out of sheer passion for a more effective cessation method. It wasn’t until 2012 that the first large tobacco company entered the vaping market. While it’s true that most every major tobacco company now has their own branded e-cigarette, these products were not created by tobacco companies to “hook future generations,” as many activists claim. Vapor products were invented by people who smoke, for themselves, because they were frustrated with the low success rates of traditional nicotine replacement products. Read more about the history of vaping and e-cigarettes.

Possibly. Heavy metals have been detected in some vapor products at varying levels, some concerning, and some not. Researchers have theorized that metals found in some products could be from the coils used to heat the liquid, however some of the testing methods used in these studies have been called into question. Overheating the coils, failing to account for metals from testing equipment, and not excluding participants who were still smoking are all potential causes of abnormally high test results.

While the presence of any level of heavy metals is certainly a concern, heavy metals are just one component contributing to the potential risks from cigarette smoke. The fact that vapor products still contain far lower levels of other carcinogens and toxins – and none of the carbon monoxide and harmful particulates – found in cigarette smoke should not be overlooked, as the overall benefits of switching to vaping still outweigh the risks of smoking. Ideally, regulation should allow manufacturers to develop products that would mitigate the risk of metals leaching into liquid.

False. This claim comes from a single defective study published in 2015 in the New England Journal of Medicine in which researchers improperly used e-cigarette devices by overheating them, and effectively “burning” the wicking material, instead of aerosolizing the liquid. This phenomenon, referred to as “dry hits” or “dry puffs,” is well known by people who use vapor products because of how harsh and intolerable the resulting vapor is. “Dry puffing” a vapor device is the only way to achieve these high levels of formaldehyde, but due to the extreme level of discomfort this is not a realistic usage scenario – the user immediately stops vaping when this happens, as it means something is wrong with the device.

This same experiment was reproduced in 2017 by researchers more familiar with how vaping devices should work, and with participation from people who vape. They found that achieving high formaldehyde levels was essentially impossible in a normal use scenario because people could not tolerate the accompanying level of discomfort and foul taste. When used properly and under normal conditions, a person’s exposure to formaldehyde from vaping is well within levels considered to be safe.

False. Vaping liquids contain the ingredient propylene glycol (PG), which is also an ingredient used in antifreeze. What this myth leaves out is that PG is also a common food additive, and it is used in antifreeze as a replacement for ethylene glycol in order to make antifreeze safer and non-toxic – especially for small children and pets.

False. E-cigarettes use lithium-ion batteries, the same battery chemistry used in many cell phones, laptops, and other consumer electronics. While battery explosions and fires can happen with any of these products (usually due to improper use or a manufacturing defect) it is generally rare.

False. This claim was largely popularized by an erroneous study published in 2019 that was subsequently retracted in 2020 (although it’s not the only one). The authors of this study claimed they found that vaping was associated with increased risk of having had a myocardial infarction, even after controlling for a history of cigarette smoking. However, what the researchers did not disclose is that the majority of the heart attacks occurred before the users started vaping, rendering the conclusions null and void, and resulting in the study being retracted by the Journal of the American Heart Association.

Nicotine use is not without risk, especially for those with pre-existing cardiovascular issues, but there is substantial evidence that switching from cigarette smoking to vaping significantly improves vascular health.

False. This claim comes from a handful of studies exposing rodents to high levels of nicotine. Mice brains are not equivalent to human brains, so this conclusion is far from solid. In fact, there is no evidence to support the idea that nicotine damages the adolescent brain. If there were it would be visible in the multiple generations of adults who began smoking as teenagers. Furthermore, there is ample research to suggest that nicotine may have some neuroprotective qualities.

Unlikely. In 2019 the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) expressed concern over a possible link between youth nicotine vaping and seizures, but no causal link has ever been established. Nicotine inhaled from tobacco cigarettes has never been shown to cause seizures, so it seems unlikely that nicotine inhaled from e-cigarettes would, especially since vapor products do not deliver the same nicotine yield as cigarettes. Additionally the evidence gathered by FDA consisted of only 122 reports gathered over 9 years, and the cases varied widely in the timing of the seizures in relation to vaping.

False. There are no confirmed cases of popcorn lung (bronchiolitis obliterans) in people who use e-cigarettes, and there is no evidence that e-cigarettes could cause popcorn lung. The name comes from an incident involving a group of popcorn factory workers breathing in a chemical called diacetyl who developed this rare condition. Diacetyl was an ingredient used in many vaping liquids, but due to an overabundance of caution most manufacturers no longer use it. Additionally, combustible cigarettes contain much higher levels of diacetyl than vapor products ever did, and popcorn lung has never been associated with smoking.

False. The CDC identified the cause of poorly named EVALI (Electronic Cigarette, or Vaping product use-Associated Lung Injury) in December of 2019 as “exposure to THC-containing vapor products that also contained Vitamin E acetate.” Lung injuries were not caused by nicotine-containing e-cigarettes. Conflating THC vapor products with nicotine vapor products in the case of EVALI is comparable to blaming all leafy-green vegetables for an outbreak of e-coli, when it’s really just a bad batch of spinach. It is unscientific, wholly inaccurate, and not consistent with CDC’s protocols for communications about an outbreak of disease.

False. This claim comes from a single mathematically flawed study published in 2020 in the Journal of Adolescent Health. Researchers gathered data from an anonymous and self-reported online survey and claimed that “e-cigarettes and cigarettes are significant underlying risk factors for COVID-19.” However, they later recanted and admitted “our study does not imply causality” after other researchers heavily criticized the study’s math and methods. A much larger study, conducted by the Mayo Clinic, found no increased risk of COVID-19 in people who vape.

Multiple countries have reported unusually low rates of severe COVID-19 in people who smoke, leading some researchers to begin studying if nicotine can be a potential therapeutic option or provide a protective effect against contracting the disease to begin with.

Unlikely. A variety of air quality tests have been performed by researchers, state health departments, and even the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services inside vapor product stores – where exposure should arguably be the highest. All the reports consistently found that concentrations of vaping-related chemicals in the air were below occupational exposure limits or not detectable at all, including nicotine, flavoring chemicals, and formaldehyde.

False. This claim comes from data showing that youth who experiment with cigarette smoking are likely to experiment with vaping, and vice versa. There is currently no data to support a causal link between the two, let alone a “gateway” effect. In fact, youth smoking rates have fallen to historic lows, even as youth experimentation with e-cigarettes has increased in some recent years. According to the latest research, the most likely causal link between vaping and smoking is that vaping is diverting young people from experimenting with smoking.

False. While it’s true that youth experimentation with vaping did increase in 2018 and 2019, it actually decreased in 2020 (data was collected before the COVID-19 pandemic). Additionally, the data most often reported only covers experimentation (trying vaping –even one puff – in the last 30 days), not regular or habitual use. Daily use of vapor products by adolescents remains relatively low, under 5% as of 2020.

False. Flavored vape products, including fruit, candy, and dessert flavors, were designed by and for adults. Surveys of adult vapers clearly show a strong preference for fruity, dessert, and sweet/candy flavors over all other flavor categories. Additionally, several researchers have noted that the “use of fruit and other sweet flavored e-liquids positively related to smokers’ transition away from cigarettes.”

We Can't Do It Without Your Support

We rely on donations from generous supporters like you.

Every little bit helps!